A good trap has personality. A good trap feels like a malign force, a cruel enemy with a vicious sense of humour. A good trap seems to laugh at you even as it unleashes its several stages of lethal surprise.

A good trap has personality. A good trap feels like a malign force, a cruel enemy with a vicious sense of humour. A good trap seems to laugh at you even as it unleashes its several stages of lethal surprise.The Chamber of Statues doesn't quite hurdle that bar. It's a little charmless, and it's competent rather than clever, but it nevertheless succeeds in providing a reasonable non-combat challenge for the players.

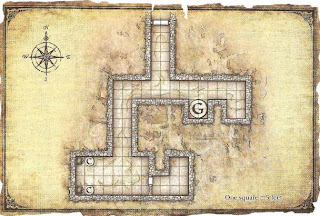

As the name suggests, this encounter is characterised by the presence of several statues. It features a gargantuan statue of a swordsman, two smaller statues of dragons, and then a collection of sculpted cherubs holding amphoras near the far door.

The room is an Obvious Trap. Players of any experience know that rooms with no visible enemies are more than they seem. When you add a collection of statues into the equation, it doesn't take a genius to see the rough shape of what's coming.

That's okay, though. Traps should speak ahead of themselves. While, strictly speaking, a completely undetectable trap is more effective, it's less dramatically interesting, and often more than a little unfair. Part of the fun of traps is knowing there's one coming, but not knowing exactly what form it will take or how to protect against it.

When players enter the room, the door locks behind them, and the big statue starts swinging its sword in a circle. Characters within its arc take damage and get knocked prone. There's only a thin space around the western edge of the room that's out of range, although there's a much larger vacant area near the dragon statues.

The dragons, naturally, are dangerous too. When PCs step between them and the swordsman, the dragons fire a force blast which pushes those it hits back into the swordsman's reach.

One place where this encounter falls short is in disarming the trap. A good trap should have several viable paths for countering it. Here avoidance is a good strategy, but players may also want to attack the statue or attempt to disarm it. The module provides rules for both these ideas, but both the difficulty and the amount of time required for success make them all but useless. Players who try to think outside the box will be brutally shut down if the encounter is run as printed.

Once players have passed the swordsman and dragons, they come to the water-bearing cherubs. Once a player has stepped between the cherubs, a magical curtain of force descends, sealing them in the area near the door (which is of course locked), and an unending torrent of magical water starts spilling from the amphoras. In three rounds it reaches a sufficient height to fully submerge the trapped player, and then commences rotating like a whirlpool, smashing its victim against the walls.

The trap falls down a little here too. Getting out of the water trap involves either smashing the cherubs, "disarming" them with Thievery, or "unmagicking" them with Arcana. It's not immediately obvious, without a little DM prompting, that the cherubs protrude through the magical barrier, allowing players outside the trap to help, nor is it clear how Thievery might help in overcoming what is apparently a magical trap. The solution is neither intuitive nor logical, which makes it that much less satisfying when you hit upon it.

Furthermore, the trap reckons without the Eladrin fey step power. In the second group that I saw attempt this room, the victim was an Eladrin fighter, who was able to contemptuously teleport to safety and watch the trap rather pathetically attempt to drown an empty room.

In any case, assuming the players actually do attempt to break the cherubs to stop the trap, they'll discover that the dragon statues have a magically increased range once the water trap is activated, and each interference with the cherubs provokes another force blast. It's challenging, but it's also frustrating and more than a little cheap.

Players who eventually overcome the combination of traps might well be asking exactly how Kalarel and his minions deal with this room on a daily basis, given it's the only way into the final chambers of Kalarel's lair. The answer is simple, explains the module - the traps only target non-evil creatures, duh.

Possibly if Kalarel was spending less time sculpting massive magical statues of swordsmen and building pretty little stone angels, he might have already opened the rift to the Shadowfell and made this whole business redundant.